either by hiding truthful information or showing false in- formation. Deception is an act of deceit with

implied intent (e.g., telling the user the web page is 70% loaded when we know that this is not the case).

On the other hand, decep- tive(ness) does not require intent (e.g., telling the user that the web page is

absolutely 70% loaded based on some esti- mate with high error margins). Though this distinction is

important as it speaks to motive, deceit exists with or with- out intent. In fact, when deciding whether an

advertisement is illegal (false), the FCC only considers the deceptiveness of the message irrespective of

intent. That said, proving motive/intent in a design is also a very convincing argu- ment for conviction.

There is a notable difference between unintentional bugs, errors, or bad metaphors and ones that have

been carefully designed for specific purposes.

Benevolent deception is ubiquitous in real-world system designs, although it is rarely described in such terms. One example of benevolent deception can be seen in a robotic physical therapy system to help people regain movement following a stroke [8]. Here, the robot therapist provides stroke patients with visual feedback on the amount of force they exert. Patients often have selfimposed limits, believ- ing, for example, that they can only exert a certain amount of force. The system helps patients overcome their percep- tive limits by underreporting the amount of force the patient actually exerts and encouraging additional force.

It is further useful to distinguish between deceit that affects behavior directly or indirectly (by modifying

the user’s mental model). A test of this impact is whether a user would behave differently if they knew the

truth. Though theline is fuzzy, this distinction allows us to separate abstrac- tion from deception. Applying

this thought experiment to deception interfaces, one might see that the 1ESS user who was connected to

the wrong number might begin to blame and mistrust the system, the rehabilitation user may recali- brate

what is on the screen and again be unwilling to push themselves, and so on. Though the line is fuzzy, this

dis- tinction allows us to separate abstraction (or simplification), in which user behavior is largely

unchanged, from decep- tion, in which it often is changed.

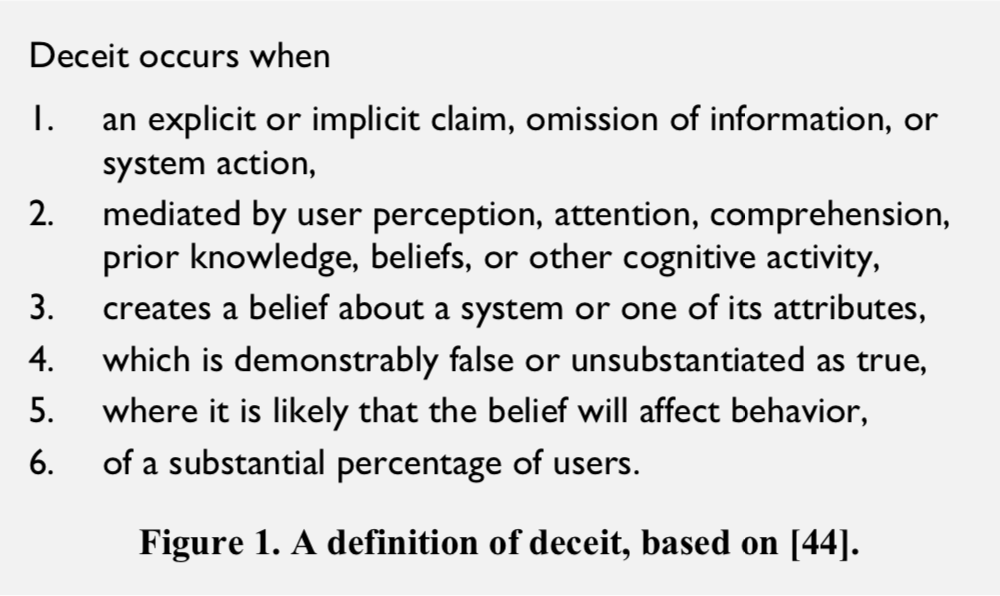

Building on behavioral and legal definitions introduced in earlier work [44] that deal with deceptive

advertising, we put forth a working definition of deceit as it applies to HCI work in the Figure 1. Points 5 &

6, on substantial effect, are perhaps the most controversial, and are purposefully left ambiguous. How

behavior is affected and what “substan- tial” means are left open, as there is likely no answer that works in

every situation. A deceptive interface that causes physical harm in 1% of the user population may have a

sub- stantial effect, whereas an idempotent interface with a but- ton that misleads significantly more users

into clicking twice may not pass the substantial test.

In addition to intent, there are many other ontologies of deceit. Bell and Whaley [4] identify two main

types of de- ception—hiding and showing—which roughly correspond to masking characteristics of the

truth or generating false information (both in the service of occluding the truth). These forms of deception

represent atomic, abstract notions of deceit that we refine in our discussion below. Related to the hiding/

showing dichotomy is the split between silent (a deceptive omission) versus expressed deception. Lying,

as a special class, is generally considered to be a verbal form of deception [5]. Because HCI need not

involve a verbal ele- ment, we expand the notion of the “lie” to include non- verbal communication

between humans and computers.