Users generally trust computer interfaces to accurately re- T system state. Reflecting that

state dishonestly— through deception—is viewed negatively by users, rejected by

designers, and largely ignored in HCI research. Many believe outright deception should

not exist in good design. For example, many design guidelines assert: “Do not lie to

your users” (e.g., [40, 45]) Misleading interfaces are usually attributed to bugs or poor

design. However, in reality, de- ceit often occurs both in practice and in research. We

con- tend that deception often helps rather than harms the user, a form we term

benevolent deception. However, the over- loading of “deception” as entirely negative

coupled with the lack of research on the topic, makes the application of de- ception as a

design pattern problematic and ad hoc.

plored features that enable this type of deception. While research into human-to-human

deception has advanced our understanding of deception in general, it has largely focused

on communication behavior that pre-exists, and per- sists through, computermediated-communication.

Most of the systematic research in the academic HCI com- munity focuses on

malevolent deception, or deception in- tended to benefit the system owner at the

expense of the user [14]. Such research frames deception negatively, and focuses on

detection and eradication of malicious or evil interfaces (e.g., dark-patterns [17]). Such

patterns include ethically dubious techniques of using purposefully confus- ing

language to encourage the addition of items to a shop- ping cart or hiding unsubscribe

functionality. Many forms of malevolent deception, such as phishing and other fraud, is

in clear violation of criminal law.

Deceptive practices that are considered harmful by legal organizations are, for

generally good reasons, considered harmful by designers as well. A possible exception

to the negative frame for malevolent deception is in contexts where an obvious

adversary exists or for military or securi- ty purposes. For example, to detect network

attacks or illicit use, security researchers may deploy “honeypots” to imitate vulnerable

plored features that enable this type of deception. While research into human-to-human

deception hcceptable even when it might affect legitimate clients who try to connect

even though no services are available.

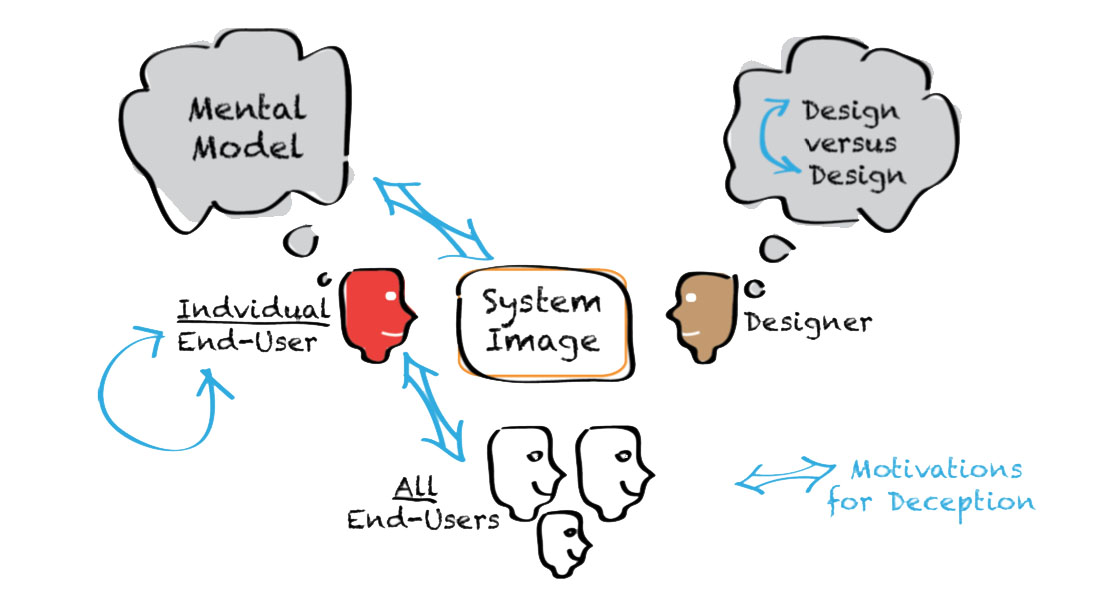

It can be difficult to draw the line between malevolent and benevolent deception. We

frame the distinction from the end-user’s perspective: if the end-user would prefer an

ex- perience based on the deceptive interface over the experi- ence based on the

“honest” one, we consider the deception benevolent. Note that this includes situations

in which both the system designer and the end-user benefit from the de- ception,

something economists sometimes term a Pareto white lie [19]. Arguably, all benevolent

deceptions that im- prove user experience benefit the interface creator as well;

otherwise, we might use the term altruistic deception [19].

The limited HCI research that has been conducted on be- nevolent deception has

focused on the use of magic [54], cinema and theater [32] as instructional metaphors for

HCI design. By using deception for the purpose of entertain- ment, playfulness, and

delight, it becomes acceptable. This work has connected these art forms, in which

illusion, im- mersion, and the drive to shape reality dominate, to situa- tions in which

there is willing suspension of disbelief on the part of the user, or at least willing pursuit

of acceptable mental models. Similar lessons have been drawn from ar- chitecture. For

example, theme parks and casinos [20, 34, 37] are designed specifically to utilize

illusions that manip- ulate users’ perception of reality, entertainment, and partic- ipation

in the experience. In this paper, we will describe a number of deceits in HCI systems

that have parallel designs to magic, theater, and architecture. However, not all benevolent

deceit can be framed in terms of creating delight for

as advanced our understanding of deception in general, it has largely fo- cused on

communication behavior that pre-exists, and per- sists through, computer-mediatedcommunication.

Most of the systematic