1. The Grand Design

1.1 First principles

1.1.1 TYPOGRAPHY EXISTS TO HONOR CONTENT

Typography exists to honor content. Like oratory, music, dance, calligraphy - like anything that lends its grace to language - typography is an art that can be deliberately misused. It is a craft by which the meanings of a text (or its absence of meaning) can be clarified, honored and shared, or knowingly disguised.

In a world rife with unsolicited messages, typography must often draw attention to itself before it will be read. Yet in order to be read, it must relinquish the attention it has drawn. Typography with anything to say therefore aspires to a kind of statuesque transparency. Its other traditional goal is durability: not immunity to change, but a clear superiority to fashion. Typography at its best is a visual form of language linking timelessness and time.

One of the principles of durable typography is always legibility; another is something more than legibility: some earned or unearned interest that gives its living energy to the page. It takes various forms and goes by various names, including serenity, liveliness, laughter, grace and joy.

One of the principles of durable typography is always legibility; another is something more than legibility: some earned or unearned interest that gives its living energy to the page. It takes various forms and goes by various names, including serenity, liveliness, laughter, grace and joy. These principles apply, in different ways, to the typography of business cards, instruction sheets and postage stamps, as well as to editions of religious scriptures, literary classics and other books that aspire to join their ranks. Within limits, the same principles apply even to stock market reports, airline schedules, milk cartons, classified ads. But laughter, grace and joy, like legibility itself, all feed on meaning, which the writer, the words and the subject, not the typographer, must generally provide.

In 1770, a bill was introduced in the English Parliament with the following provisions:

... all women of whatever age, rank, profession, or degree, whether virgins, maids, or widows, that shall ... impose upon, seduce, and betray into matrimony, any of His Majesty's subjects, by the scents, paints, cosmetic washes, artificial teeth, false hair, Spanish wool, iron stays, hoops, high heeled shoes [or] bolstered hips shall incu the penalty of the law in force against witchcraft ... and ... the marriage, upon conviction, shall stand null and void.

The function of typography, as I understand it, is neither to further the power of witches nor to bolster the defences of those, like this unfortunate parliamentarian, who live in terror of First being tempted and deceived. The satisfactions of the craft come Principles from elucidating, and perhaps even ennobling, the text, not from deluding the unwary reader by applying scents, paints and iron stays to empty prose. But humble texts, such as classified ads or the telephone directory, may profit as much as anything else from a good typographical bath and a change of clothes. And many a book, like many a warrior or dancer or priest of either sex, may look well with some paint on its face, or indeed with a bone in its nose.

1.1.2 LETTERS HAVE A LIFE AND DIGNITY OF THEIR OWN.

Letterforms that honor and elucidate what humans see and say deserve to be honored in their turn. Well-chosen words deserve well-chosen letters; these in their turn deserve to be set with affection, intelligence, knowledge and skill. Typography is a link, and it ought, as a matter of honor, courtesy and pure delight, to be as strong as the others in the chain.

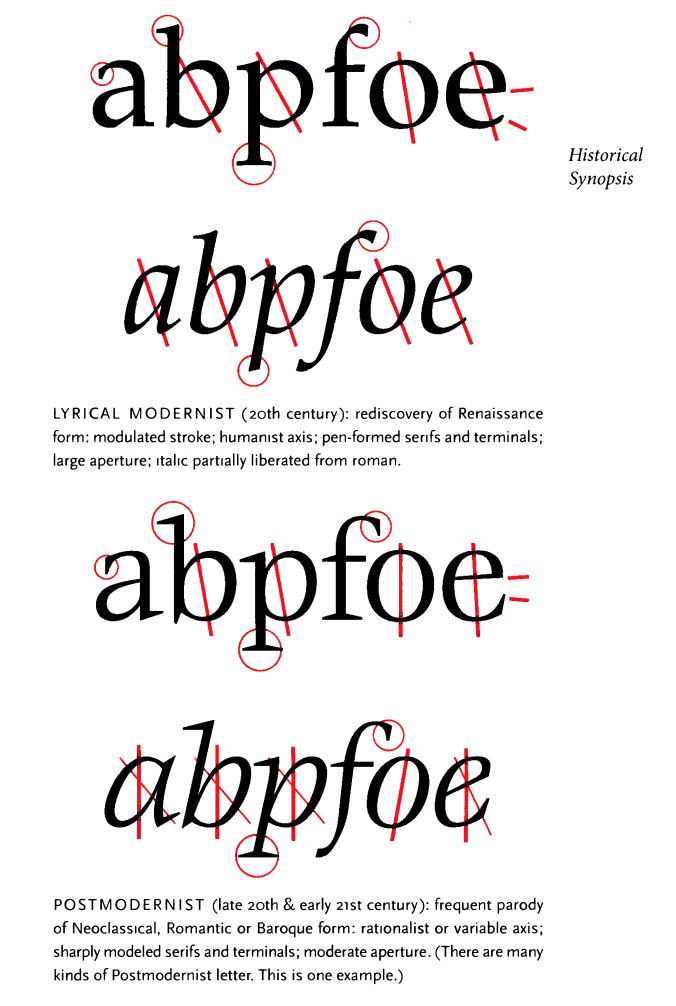

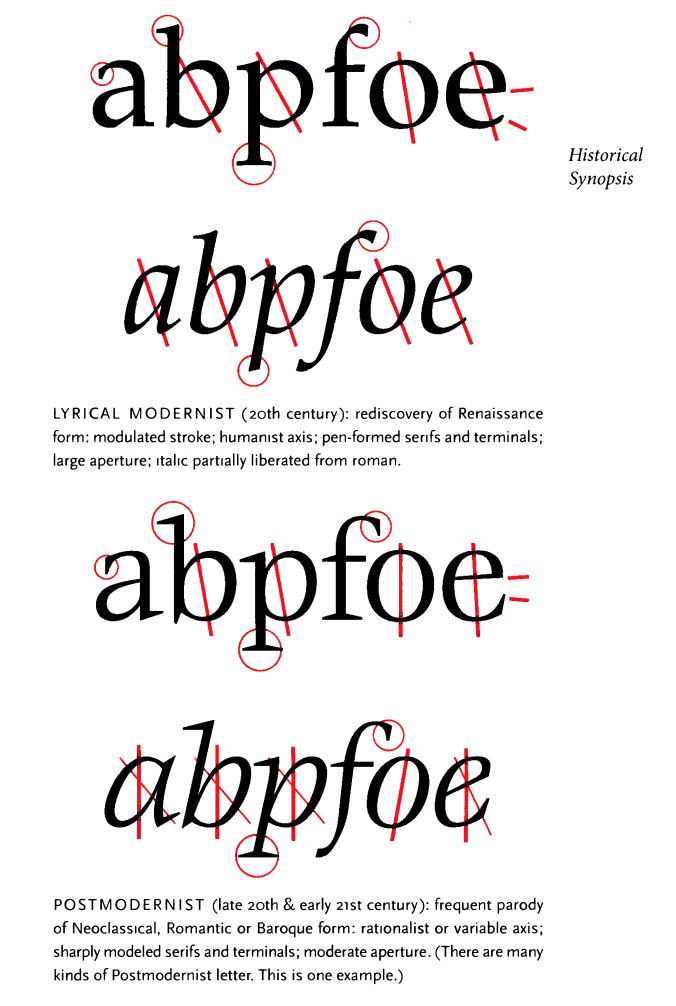

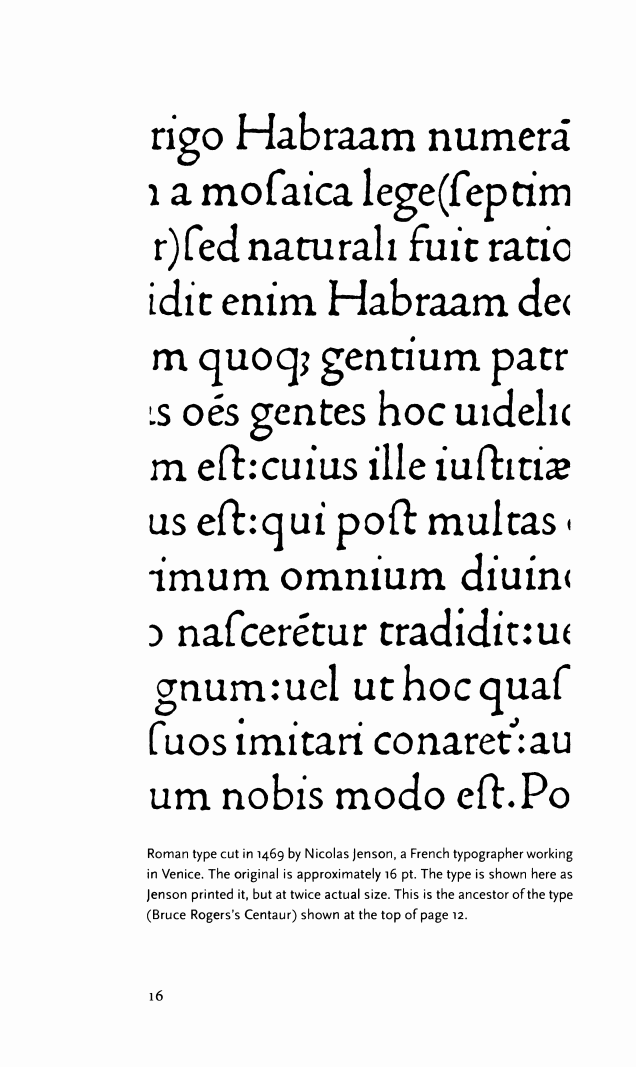

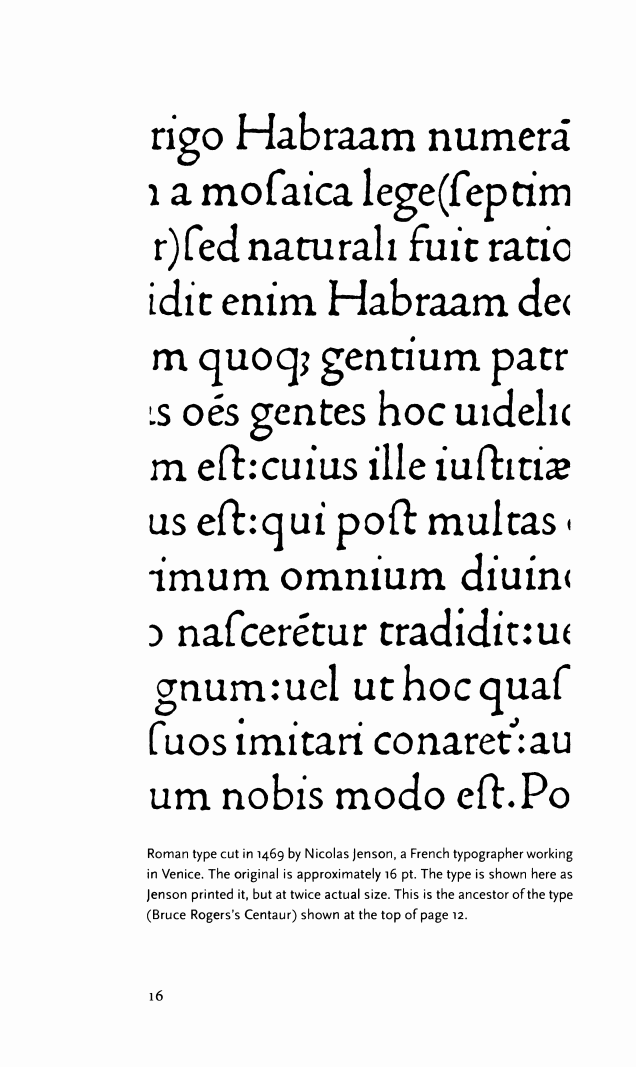

Writing begins with the making of footprints, the leaving of signs. Like speaking, it is a perfectly natural act which humans have carried to complex extremes. The typographer's task has always been to add a somewhat unnatural edge, a protective shell of artificial order, to the power of the writing hand. The tools have altered over the centuries, and the exact degree of unnaturalness desired has varied from place to place and time to time, but the character of the essential transformation between manuscript and type has scarcely changed.

The original purpose of type was simply copying. The job of the typographer was to imitate the scribal hand in a form that permitted exact and fast replication. Dozens, then hundreds, then thousands of copies were printed in less time than a scribe would need to finish one. This excuse for setting texts in type has disappeared. In the age of photolithography, digital scanning and offset printing, it is as easy to print directly from handwritten copy as from text that is typographically composed. Yet the typographer's task is little changed. It is still to give the illusion of superhuman speed and stamina - and of superhuman patience and precision - to the writing hand.

Typography is just that: idealized writing. Writers themselves now rarely have the calligraphic skill of earlier scribes, but they evoke countless versions of ideal script by their varying voices and literary styles. To these blind and often invisible visions, the The typographer must respond in visible terms.

Grand In a badly designed book, the letters mill and stand like Design starving horses in a field. In a book designed by rote, they sit like stale bread and mutton on the page. In a well-made book, where designer, compositor and printer have all done their jobs, no matter how many thousands of lines and pages they must occupy, the letters are alive. They dance in their seats. Sometimes they rise and dance in the margins and aisles.

Simple as it may sound, the task of creative non-interference with letters is a rewarding and difficult calling. In ideal conditions, it is all that typographers are really asked to do - and it is enough.

1.1.3 THERE IS A STYLE BEYOND STYLE.

From part 2 of Benjamin's essay on Karl Kraus, in lluminationen(Frankfurt, 1955). There is an English translation in Walter Benjamin, Reflections, ed. Peter Demetz (New York, 1978).

Literary style, says Walter Benjamin, "is the power to move freely in the length and breadth of linguistic thinking without slipping into banality:' Typographic style, in this large and intelligent sense of the word, does not mean any particular style - my style or your style, or Neoclassical or Baroque style - but the power to move freely through the whole domain of typography, and to function at every step in a way that is graceful and vital instead of banal. It means typography that can walk familiar ground without sliding into platitudes, typography that responds to new conditions with innovative solutions, and typography that does not vex the reader with its own originality in a self-conscious search for praise.

Typography is to literature as musical performance is to composition: an essential act of interpretation, full of endless opportunities for insight or obtuseness. Much typography is far removed from literature, for language has many uses, including packaging and propaganda. Like music, it can be used to manipulate behavior and emotions. But this is not where typographers, musicians or other human beings show us their finest side. Typography at its best is a slow performing art, worthy of the same informed appreciation that we sometimes give to musical

performances, and capable of giving similar nourishment and

pleasure in return.

The same alphabets and page designs can be used for a biography of Mohandas Gandhi and for a manual on the use and deployment of biological weapons. Writing can be used both for love letters and for hate mail, and love letters themselves can be used for manipulation and extortion as well as to bring delight to body and soul. Evidently there is nothing inherently noble and trustworthy in the written or printed word. Yet generations of men and women have turned to writing and printing to house and share their deepest hopes, perceptions, dreams and fears. It is to them, not to the extortionist - nor to the opportunist or the profiteer - that the typographer must answer.

1.2 Tactics

1.2.1 READ THE TEXT BEFORE DESIGNING IT.

The typographer's one essential task is to interpret and communicate the text. Its tone, its tempo, its logical structure, its physical size, all determine the possibilities of its typographic form. The typographer is to the text as the theatrical director to the script, or the musician to the score.

1.2.2 DISCOVER THE OUTER LOGIC OF THE TYPOGRAPHY AND THE INNER LOGIC OF THE TEXT

A novel often purports to be a seamless river of words from beginning to end, or a series of unnamed scenes. Research papers, textbooks, cookbooks and other works of nonfiction rarely look so smooth. They are often layered with chapter heads, section heads, subheads, block quotations, footnotes, endnotes, lists and illustrative examples. Such features may be obscure in the manuscript, even if they are clear in the author's mind. For the sake of the reader, each requires its own typographic identity and form. Every layer and level of the text must be consistent, distinct, yet (usually) harmonious in form. The first task of the typographer is therefore to read and understand the text; the second task is to analyze and map it. Only then can typographic interpretation begin. If the text has many layers or sections, it may need not only heads and subheads but running heads as well, reappearing on every page or two-page spread, to remind readers which intellectual neighborhood they happen to be visiting.